The story is ubiquitous. Queen Margherita of Savoy, royal consort to King Umberto I, was visiting the palace at Capodimonte in Naples. Having grown tired of the French cuisine enjoyed by European royalty, she decided she’d like to taste to food of the common people: pizza. Her staff summoned a famous pizza maker named Rafaele Esposito to bake for the queen. Esposito served her three pizzas: the mast’nicola (lard, basil, and hard cheese), the marinara (tomato, garlic, small fish, and herbs), and the pizza alla mozzarella (tomato and mozzarella). Just as he was about to serve that final pizza, his wife Maria Giovanna Brandi noticed that the red of the tomato and the white of the mozzarella would be perfectly complimented by a couple leaves of basil, allowing it to resemble the Italian flag. What a lovely gesture! The queen adored all three pizzas but loved the final one most of all, so Esposito dubbed it Pizza Margherita.

Some stories say that Esposito was summoned to the palace at Capodimonte, others say the queen ventured to his pizzeria, which was at that time called Pizzeria della Regina d’Italia aka Pizzeria of the Queen of Italy. As you can see, Esposito was a real fanboy. The pizzeria is now called Pizzeria Brandi (renamed by Maria Giovanna Brandi’s nephews after they took over the restaurant in the 1930s) and they proudly boast about the famous story with images of the queen adorning the interior walls and a very official looking plaque commemorating the centennial of the Pizza Margherita naming on the pizzeria’s facade.

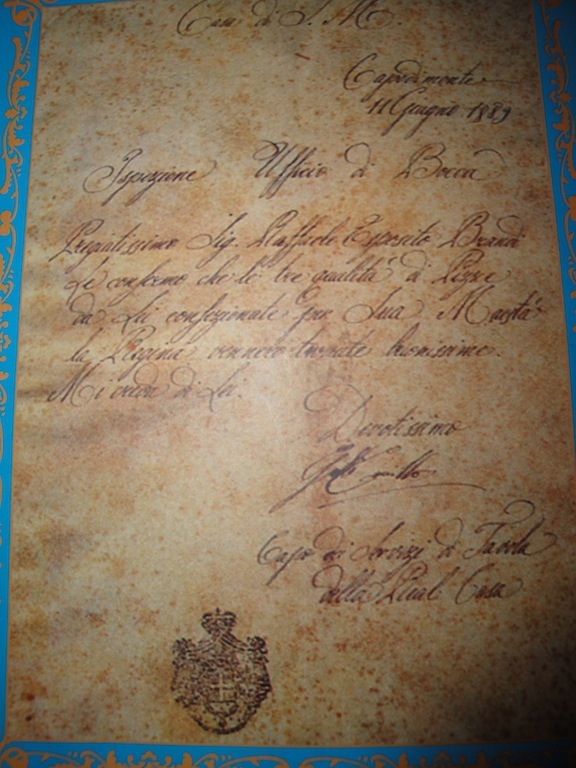

Unfortunately, no newspaper reported about the pizza party it at the time. But Pizzeria Brandi does have a thank you note from Queen Margherita’s handlers showing gratitude for the pizza made by Rafaelle Esposito. The letter is dated 11 June, 1889 and serves as the only evidence of the encounter.

Here’s the translation:

From the Office of the Mouth

Most esteemed Mr Raffaele Esposito Brandi. I confirm to you that the three kinds of pizza you prepared for Her Majesty the queen were found to be delicious.

Please believe me to be

Your most devoted servant,

Galli Camillo

Head of Table Services to the Royal Household

But there’s a problem. Actually, there are several problems. This letter, the only evidence of the fateful transaction, is a fraud. The truth was uncovered by historian Zachary Nowak and is detailed here on his website. I strongly suggest you read Nowak’s words from his website, but here’s the summary.

- The royal seal on the letter is in the wrong place.

- The signature of the “Head of Table Services,” one Galli Camillo, doesn’t match other signatures on file in Italian archives.

- The name of the pizza maker isn’t correct. His name was Raffaele Esposito, but the letter calls him Raffaele Esposito Brandi.

- The letter doesn’t mention details about any of the pizzas or an indication of which pizza the queen preferred.

While it’s entirely possible that the event happened and that a thank you note was written, this particular letter does not appear to be the genuine article. We may gain some clarity from other elements of context. For instance, a wine merchant by the name of Raffaele Esposito requested permission to use the royal seal of the queen at his shop in 1871. If it’s the same Esposito of the pizza story, we have ourselves a clue! We already know from the name of his pizzeria that Esposito was a fan of the monarchy (or at least he saw marketing value in it). Nowak’s research uncovered that Maria Giovanna Brandi’s family were pizza makers and that likely influenced Esposito’s profession after their marriage in 1877. He purchased an existing pizzeria in 1883, then called Pizzeria di Pietro e basta così, before renaming it Pizzeria della Regina d’Italia.

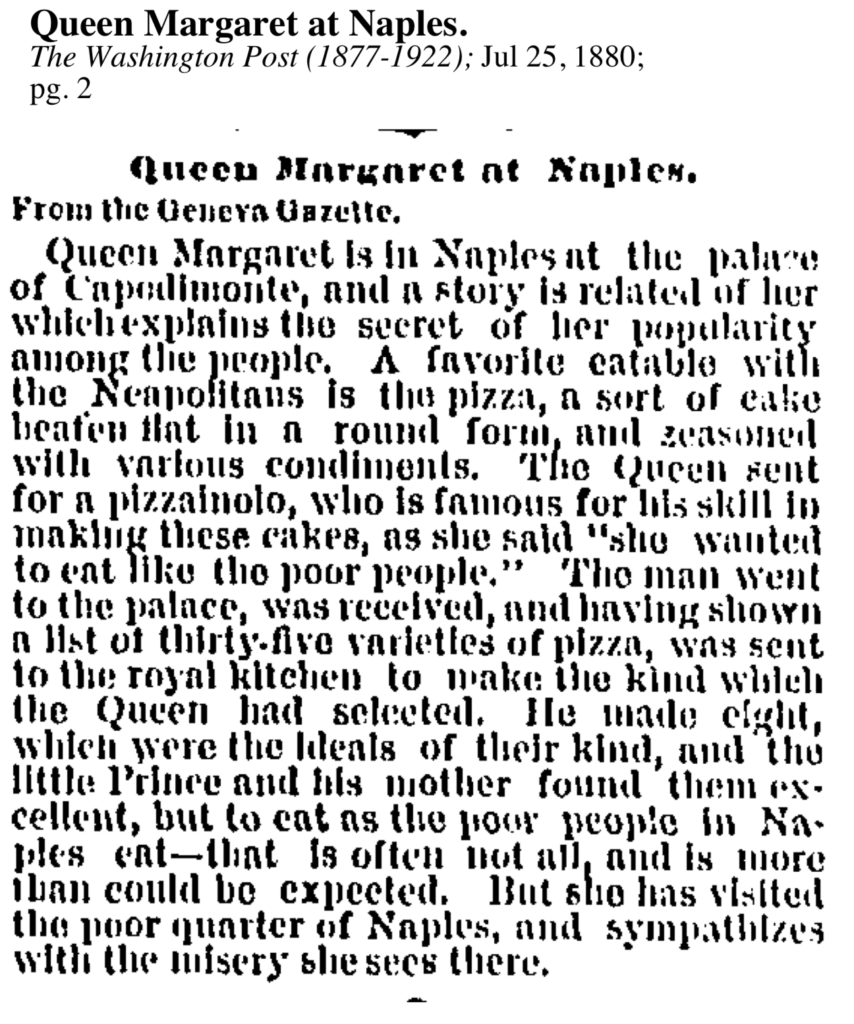

Enter into the mix another confusing twist to the story offered by this article from The Geneva Gazette (reprinted by the Washington Post on July 25, 1880). It tells of Queen Margaret visiting Naples and gaining popularity by eating pizza, “a sort of cake beaten flat in a round form, and seasoned with various condiments.” As you’ll read below, the queen sends for a famous pizza maker, who visits Capodimonte and offers her a menu of 35 different choices. Familiar story, isn’t it? This article was published 9 years before the famous thank you note was written, which means the queen was already a pizza fan before Raffaele Esposito even bought his pizzeria.

Neapolitans adore stories about monarchs eating pizza. King Ferdinand is said to have had a pizza oven built at Capodimonte, perhaps the same oven that some say was used to make pizza for Queen Margherita. Even today any pizzeria that has ever served a dignitary or politician boasts about it. After Bill Clinton at pizza at Pizzeria di Matteo while visiting Naples for the G7 summit in 1994, the owner’s brother split off and opened another pizzeria down the street, dubbed Pizzeria dal Presidente. Pizza has always been a food of the poor, even ridiculed in several pieces of writing throughout the 19th century, so there’s some symbolism behind it being enjoyed by the upper class. Even over a century later, the image of pizza is one of causality and relaxation.

Even if the 1889 letter is a fraud, it doesn’t absolutely prove that Raffaele Esposito didn’t make pizza for the queen and subsequently name it after her. After all, we don’t see use of the name Pizzeria Margherita before 1889. Then again, we don’t see that term in use until decades later. And there’s plenty of evidence of tomato, mozzarella, and basil coexisting on pizza before 1889, so those who attribute this date to the invention of the modern pizza are clearly incorrect. It’s even likely that the menu of 35 pizzas offered to the queen in 1880, maybe even one of the eight she selected, became the famous Pizza Margherita we know and love today. But if Esposito didn’t buy his pizzeria until 1883, it’s unlikely he made the pizza enjoyed by the queen in 1880.

So where does that leave us? Pizza Margherita is clearly responsible for setting the standard by which we define all pizza today, but it wasn’t invented in 1889 and we certainly don’t have evidence of when and why it was given its name. The story of the queen is certainly a lovely one and you’re likely to hear it far more often than the fact-based version uncovered by Nowak’s research, but sometimes mystery is more interesting than truth.

FOR ADDITIONAL INFORMATION:

Delizia! The Epic History of the Italians and Their Food by John Dickie

Garlic & Oil: Food and Politics in Italy by Carol Helstosky

Inventing the Pizzeria by Antonio Mattozzi

How Italian Food Conquered the World by John F. Mariani