This is the first in a series of posts about my recent trip to Italy.

On my first pilgrimage to Naples, I visited dairies, farms, orchards and a ton of historic pizzerias. When I got back home and reviewed all my photos, I realized I had missed out on the most basic element of pizza: flour. I was embarrassed. Exactly one week ago today, I returned from a Neapolitan vacation with fellow pizza enthusiast Jason Feirman and we spent Day 1 at the highest regarded flour mill in Naples.

The name Caputo is no stranger to the American pizza scene, being an essential ingredient of wood-fired Neapolitan pizzerias that seem to be opening across the country faster than you can say “mozzarella!” We started with a lesson in wheat, which completely blew my mind. Caputo purchases wheat from all around the world because each country’s crop provides different levels of protein. The samples are then blended and milled depending on the desired specifications of the product coming off the line on a particular day. It’s easy to see the difference between wheat samples in the photo to the right, which features the hands of Antimo Caputo, whose grandfather (also named Antimo) opened the mill in 1924. By using so many different wheat sources, Caputo is able to product a wide variety of products without the use of any additives or supplements.

Antimo’s cousin Mauro took over the tour and brought us into the actual milling facility. The building is separated into three levels: 1. shipping/receiving, 2. grinding and 3. shaking. All this hoopla results in an extremely fine all natural flour. Most flour companies add protein and minerals to replace those lost in the milling process but Caputo’s flour remains all natural thanks to the employment of fewer, more delicate stages. The photograph below shows two stages of the milling process. You can see that the sample to the right is much finer than the sample to the left. At the very end of the process, all bran and germ are filtered out and the result is bright white. Rather than trash the leftover scraps, Caputo sells it to farms to be used as animal feed. No waste!

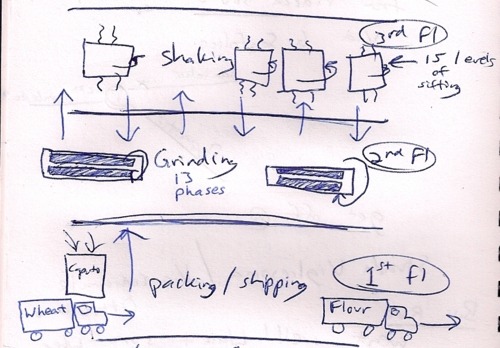

The mill is organized vertically, which has been par for the course since the late 19th century. Wheat is brought into the first level and sucked through tubes to the upper floors of the facility. You can see the grated floor behind Jason and Mauro in the photo above. The wheat then bounces between the second and third floor as it gets crushed and shaken before heading back down to the packing/shipping area. It’s pretty simple, but this page I scanned from my travel journal might help you visualize the whole deal.

Quick, go home and build your own Caputo mill before they force me to take down this highly detailed diagram!

All of Caputo’s flour is considered “00” because of how finely it’s milled. Some people think this it means it is low in protein, but the two designations are not related. Caputo offers about a dozen products with varying degrees of protein and all of them are considered “00.” At Caputo, a product’s protein count is dependent on the wheat samples of which it is composed and each product has its own intended application. Neapolitan pizza is greatly dependent on “00” flours, which are necessary to produce a light, fluffy crust after spending 60-90 seconds in a wood-fired oven. Most of the pizzerias we visited in Naples use “00” flour and many used Caputo.

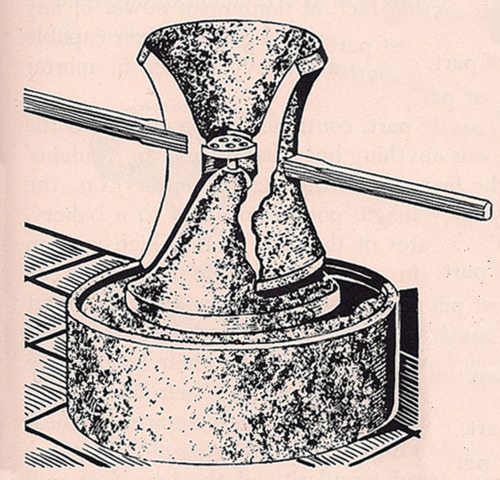

But the mill tour made me wonder what flour would have been like in the days prior to multinational wheat trade and vertical milling facilities. Antimo reminded me that flour was very roughly milled between stones in the early 16th century when early pizzas were being made in Southern Italy, rendering “00” virtually impossible to produce. The reality struck me when I was checking out Herculaneum a few days later. Just like Pompeii, Herculaneum was destroyed by the eruption of Mt. Vesuvius in 79 A.D. Thanks to its position further down the volcanic slope, Herculaneum is in much better shape than Pompeii. I tracked down the town’s mill and found this incredibly well-preserved setup.

In this two-part device, the top piece (catillus) is mounted on the base (meta). Wheat is poured through the opening on top and emerges around the bottom after being pulverized. The photo on the left shows an exposed meta in the foreground and an assembled catillus and meta in the background. Yes, I am aware of how phallic this looks. But my photo isn’t nearly as descriptive as this sweet diagram I found in Flour for Man’s Bread by John Storck and Walter Dorwin Teague (illustrated by Harold Rydell). This textbook was published by University of Minnesota Press in 1952 and it presents a detailed history of milling. I totally freaked out when I found a picture of an “hourglass mill” just like the one I saw in Herculaneum.

Even though this 2000 year old mill was obsolete by the time pizza was flooding the streets of Naples in the 18th century, the concept isn’t far off. Ancient pizza flour would have contained some germ and bran, much like today’s whole wheat options. So next time you’re chowing down on some whole wheat crust, think about how much you may have in common with the world’s first pizza enthusiasts!